Is survival the industry's new mantra?

The dynamics between the submarine carriers that own today's high-risk, underutilized transoceanic systems can best be described as "co-opetition."

JULIAN RAWLE, Pioneer Consulting

Cable operator 360networks' recent announcement of the cancellation of its planned transpacific and pan-Asian cables, followed by a default on its bond interest payments, is the first clearly visible sign that the submarine telecommunications cable industry is entering a new and more difficult phase of development. How are the cable owners going to adjust to the new economic realities? And what effect will changes in their strategic direction have on their suppliers?

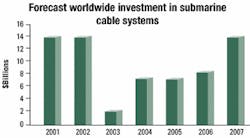

In the two-year period leading up to the end of 2002, a staggering $28 billion will have been invested in submarine cable systems around the world. This amount compares with an average of $9.2 billion per year from 1988 to 2000, which is in itself a huge sum.The finance markets today look at the telecommunications sector and see inflated prices paid for 3G mobile licenses, delays in delivering broadband-enabling DSL technology to the local loop, and companies failing to make their forecast revenue figures. It is no wonder that enthusiasm for investing in submarine cables has also waned.

Add to this the fact that by the end of 2003, only 14% of the total submarine capacity in the water will actually be lit and generating a revenue stream, and you have all the ingredients for an industry recession, cash flow crises, company restructuring, and even failure.

Figure 1 shows Pioneer Consulting's forecast of investment in submarine cable systems until 2007. As Figure 1 indicates, 2003 will be an exceptionally difficult year for any company that derives its revenue from the submarine cable industry.

Subsequently, investment levels will recover up to around the annual average, as growth in Internet demand requires capacity upgrades to existing cables. Since terminal station equipment (especially DWDM) now constitutes about 50% of the total value of a long-haul cable system, it will provide a welcome revenue stream to the equipment vendors. The marine contractors, however, will not have this cushion to fall back on. Only in 2007 will there be a level of investment in submarine cables similar to today's.

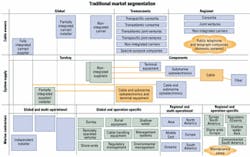

Figure 2 shows what the submarine cable market looks like today. The market consists of three levels: the cable owners, the system suppliers, and the marine contractors.

The cable owners initiate and obtain funding for cable projects in order to capture and transport specific streams of revenue-generating telecommunications traffic between markets. A modern transoceanic system will cost between $1 billion to $2 billion, so the cable owner's risk exposure is large. Cable owners are characterized according to the footprint of their network as global, transoceanic, or regional.The system suppliers, or vendors, that supply the various equipment-fiber, cable, terminal equipment, and submarine optoelectronics-can be characterized as either turnkey or component suppliers. Some of the turnkey suppliers manufacture cable, while others do not. As overall project managers, the turnkey suppliers' risk is also considerable. Their contract with the cable owner generally contains a liquidated damages clause, which puts up to 10% of the contract value at risk for failure to deliver on time and requires the supplier to provide a two-year warranty on the components and the installation work.

The marine contractors provide the vessels and specialist marine tools needed to survey, design, and clear the route; install the cable and repeaters in deep and shallow water; construct the shore-ends; bury the cable where necessary; provide a post-lay inspection and reburial service; and provide ongoing maintenance cover. These companies can be characterized as global and multioperational, global and operation-specific, regional and multioperational, or regional and operation-specific. The marine contractors also operate under the threat of liquidated damages and must provide a warranty for their work.

In the past five years, dissatisfaction with the ability of the traditional consortium approach to submarine cable building to deliver customer-responsive service has led to the rise of private cable owners. Some cable owners, such as Global Crossing, set out to build an entirely global network, providing seamless ubiquity worldwide. Others, such as Cable & Wireless, continue to participate in consortium ventures but also participate in joint ventures or build their own transoceanic routes. Some regional carriers, such as SingTel and Telstra, have also decided to build regional cables.

The go-it-alone approach of the private cable owners caused the boom in cable construction from 1997 to 2002. Multiple cables have been laid along the same route, competing for the same traffic streams.Many international carriers pursue a strategy of consortium participation or straight capacity purchase, rather than building for themselves. The proliferation of cables on most key routes has provided these carriers with an enhanced choice of service and pricing level.

However, when it comes to marketing the new private cables, it has become apparent that achieving sustainable competitive advantage through product differentiation is a tricky proposition. True, by providing city-to-city or even building-to-building circuits, the private cables have a big advantage over the consortium cable which can only deliver service to the shore station or worse, to the beach manhole, and leave the customer to arrange the back-haul. The private cables can also provide dark or dim fiber, which allows the customer varying levels of management control over the circuits. That would be unthinkable in the consortium model.

The real difficulty for private cables is in competing with other private cables on the same route. Here, the ability to differentiate one's product is limited-how much better is one gigabit versus another gigabit?

The realization of this fact has led to two developments. First, private cable owners recognized that they could not compete at the physical submarine cable layer and so focused on providing differentiated services in the metro space at the ends of the cable.

Second, wherever possible, private cable owners have sought to strike deals with each other to share the risks in their long-haul submarine cables. Level 3's planned transatlantic Yellow submarine cable became two dark fiber pairs on Global Crossing's Atlantic Crossing-2 cable. TyCom's planned transpacific cable has become four dark fiber pairs on FLAG Telecom's FLAG Pacific-1 cable.

FLAG Telecom has also combined its planned pan-Asian system with Level 3's plans for the same. In this case, the two carriers each own three fiber pairs, but the system is managed and operated by FLAG Telecom. 360networks had combined its plans for a pan-Asian network and a transpacific cable with C2C (SingTel) until the former's funding ran out.

So the balance has swung back from unilateral submarine cable development toward mini-consortia, and the window of opportunity for easy funding has closed. Furthermore, the dynamics at the submarine level between the carriers that own these huge risk-laden and underutilized transoceanic systems can best be described as co-opetition.

For the period 1999-2003, Alcatel Submarine Networks' (ASN) market share of awarded worldwide submarine cable installations and upgrades is 34%. In the same period, Tyco Submarine Systems Ltd. (TSSL) has won 29% of the available business (excluding TyCom contracts). The nearest challenger to this near duopoly is Kokusai Denshin Denwa-Submarine Cable Systems (KDD-SCS) with 16%.Other major players in the systems supply market are NEC (8%) and Fujitsu (7%). Pirelli is a significant supplier of cable but is not generally the main contractor for major systems. Siemens, Ericsson, and Corning/Nord deutsche Seekabelwerke (NSW) focus on smaller regional systems.

The value of supply contracts for planned submarine cable systems that have yet to be awarded is in the region of $5 billion.

It does not take a regulator's eye to see that there is a relatively low level of competition in this market. To make matters worse, TyCom has decided to use 50% of subsidiary TSSL's cable and repeater manufacturing capacity to build its own global network between now and 2010.

TyCom's move into the carrier market also raises conflict of interest issues. Currently, the company is sitting on the fence and its customers, the carriers, are watching warily. At some point, TyCom will have to decide which market it really wants to be in.

Other than ASN, potential claimants to TSSL's relinquished market share lack the experience and credibility to be entrusted with the management of multibillion-dollar projects.

NEC caused a stir in 2000 by bidding well below market levels to win the lead contracts for APCN-2 (pan-Asian consortium cable) and for AJC (Australia-Japan mini-consortium).

Having won phase 1 of Global Crossing's East Asia Crossing, KDD-SCS lost out to NEC on phase 2. Al though the cable is operational, KDD-SCS still has to complete the final sections of TAT-14 (transatlantic consortium cable) and is also distracted by questions over its business fit with its Japanese carrier parent, KDD.

Pouring oil on troubled waters, NEC announced in early 2001 a non-exclusive alliance with Japanese cable manufacturer, Ocean Cable and Communications Corp. (OCC). This deal effectively gives NEC first refusal on all of OCC's cable production. OCC had traditionally been the prime cable supplier to KDD-SCS.

This move was in response to the shortage of cable manufacturing capacity to meet the heightened demand in 2001 and 2002. However, forecasts indicate that, based on today's worldwide cable manufacturing capacity of about 200,000 km per year, this kind of shortage will not occur again before 2007. Until that time, Pirelli, Ericsson, and Corning/NSW, as suppliers of cable, appear vulnerable.

ASN has been hurt recently, not by competition, but by the downturn in the market, which has seen at least $3.4 billion wiped off its order books for 2002 through project cancellations and amalgamations. Fujitsu has had a long association with ASN, supplying components, but has recently won in its own right the contract for Nava-1 (Australia-Jakarta-Singapore private cable). Alcatel continues to forge new strategic alliances such as the recently announced cross-licensing agreements with Corning and Sumitomo and a supply contract for laser chips and pump stabilizers with JDS Uniphase. However, Alcatel's at tempt to acquire Lucent Technologies appears to have failed for the moment.

The downturn in installation activity forecast by Pioneer for 2003 will hit all of the system suppliers hard. Nevertheless, when the capacity upgrade activity begins in 2004, TyCom's focus on its own network-build will leave ASN/Fujitsu in a good position. NEC's 2001 and 2002 order book gives the company a good chance of riding the storm. KDD-SCS appears to be in the weakest position, with few orders and a lack of strategic direction.

The fundamental problem with the marine telecommunications cable in stal lation market is that it is prone to peaks and troughs, while a marine installer's main revenue-generating assets, the ships, are depreciated over 25 years and produce a relatively low return on capital investment of about 10%.

For this reason, as deregulation takes hold in the worldwide telecommunications market and competition increases, telecommunications companies find that they can no longer support this line of business. Cable & Wireless divested its market-leading marine business to Global Crossing, which needed a fleet of ships to build and maintain their new network. The company is now known as Global Marine Systems Ltd. (GMSL) and has 24 vessels.

Telefónica sold Temasa to TyCom for the same reason and ASN has acquired Telecom Danmark's fleet, as well as British firm CTC Marine Projects. Including new builds, TyCom now has 17 ships and ASN has 14 at its disposal.

There remain a number of smaller marine contractors. France Cables et Radio (FCR) is still a subsidiary of France Telecom. Its four ships participate in major projects such as TAT-14 and Southern Cross (North America-Australia mini-consortium cable).

Elettra is a subsidiary of Telecom Italia and operates its three ships exclusively in the Mediterranean. KDD-KCS is owned by KDD. Its two ships operate mainly around Japan. KST belongs to Korea Telecom and covers the Asia-Pacific region with one ship. SBSS, with two vessels, is a Chinese joint venture managed by GMSL. Nippon Telephone and Tele graph World Engineering Marine Corp. is a joint venture between GMSL and NTT Communications and operates two vessels mainly around Japan.

Despite this plethora of small, regionally based marine contractors, marine installation contracts for major systems usually require multivessel solutions and considerable project management experience. Consequently, these smaller operators tend to be subcontracted on an as-needed basis by the big three: GMSL, TyCom, and ASN. However, the tendency for telecommunications companies to divest such assets is so strong that it can only be a matter of time before the likes of FCR, Elettra, and maybe KDD-KCS are put up for sale.

Unfortunately, this is not a good time to be selling tonnage. With the end of the peak of cable installation activity in sight for the next few years, there is a large surplus of vessels, which are going to be competing for meager pickings. With their economies of scale and long-term maintenance contracts, GMSL, TyCom, and ASN should be able to survive. Maintenance contracts, mainly from their parent companies for domestic submarine cables, will likely be the sole source of revenue for the smaller players.

Of the big three, GMSL appears the most vulnerable. Global Crossing's network build is almost complete. GMSL has a long-term contract to maintain this network but, like Cable & Wireless, Global Crossing may find its shareholders asking difficult questions about keeping an asset with such a low return on investment. Furthermore, both TyCom and ASN have begun to offer "cradle-to-grave" solutions to cable owners, taking responsibility for installing, maintaining, and ultimately decommissioning the cable. Despite an alliance with NEC and OCC, GMSL's lack of turnkey system supply capability makes it difficult to compete with such an offering.

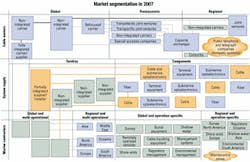

So how will competition in the different levels of the submarine telecommunications cable market affect the market's composition? Figure 3 shows Pioneer's view of what the market may look like in 2007.

Within the cable owner segment, Pioneer forecasts that capacity exchanges will come to play a pivotal role in the market. Today, these exchanges are nascent at best. Their development is being hampered by difficulties in producing standardized contracts that can guarantee a certain level of service and delivery. However, Pioneer believes that the continued collapse in bandwidth prices, driven by competition and new technology, combined with a potentially massive oversupply of capacity, will make capacity exchanges a necessary tool in the future for optimizing a carrier's network.

Pioneer also forecasts a continuation of the co-opetition, which is currently characterizing the long-haul carrier market. Some carriers with global network aspirations will be forced to refocus. These providers will either adopt a strategic mix of build and buy, or limit their geographical coverage. New global networks will not emerge in the foreseeable future.

As for the system supplier market, Pioneer does not foresee any serious challenge to the virtual duopoly of ASN and TyCom. If anything, depending on how quickly TyCom chooses to build out its own network, ASN's market share may grow.

There has been much speculation about if and when ASN will follow TyCom's lead into the carrier market. In addition to building its own network, TyCom has taken equity stakes in a number of cable systems in order to win the construction contract. ASN has tried to avoid, wherever possible, the need for supplier finance of any kind, although the company recently provided financing for Cable & Wireless' transatlantic Apollo project. It also remains to be seen how ASN will deal with the convertible bond purchased as part of a strategic alliance with 360networks, now that their partner has cancelled all further network construction.

ASN's cradle-to-grave approach has the company striking deals with carriers to provide maintenance not only of the cables, but also the terminal stations. Furthermore, ASN is trying to grow its facilities management outsourcing business, servicing the needs of new carriers that do not wish to invest in network-management resources and of incumbents that find it cost-effective to outsource management of their legacy networks. Pioneer believes that trying to copy TyCom with another global network offers no advantage to Alcatel. However, the development of an outsourced facilities management service may serve as a non-threatening back-door entry to the carrier market by Alcatel.

Only a united Japan Inc. approach from NEC, Fujitsu, and KDD-SCS could challenge ASN and TyCom. The present state of the Japanese economy could act as a stimulus for such a consolidation, but the cultures of these three organizations are so different that a merger would be fraught with difficulty.

On the other hand, Pioneer forecasts that the component supply sector will see a rash of mergers and acquisitions, driven by the need to reduce costs, achieve economies of scale, and maintain revenue flows. Lucent Technologies' recent debt-servicing difficulties are not an isolated case. A natural consequence of that will be to put the brakes on research and development of broadband technologies at a time when the market is having trouble digesting the available capacity of transoceanic cables.

Consolidation in this sector, however, will not produce a serious challenger to ASN and TyCom in the submarine cable market, because their depth of knowledge and project management experience presents a considerable barrier to entry.

While capacity upgrades will help the system suppliers survive the coming lean period, that will not provide succor for the marine sector. Pioneer forecasts that the days of the global independent marine contractor are numbered. If the system suppliers continue their strategy of vertical integration into this segment, their competitive advantage will be irresistible.

Equally, the regional marine contractors, particularly in Asia, North America, and Europe will find it difficult to obtain the necessary capital investment from their parent companies to renew their assets. Consequently, these companies will be forced to consolidate or be liquidated. Going it alone will not be an option.

"Competition" is the watchword of all free marketers. It has brought great benefits to the telecommunications user and engendered a boom in the industry. However, in the long-haul submarine cable-owning sector, it is mixed with a heavy dose of cooperation. In the systems supply and marine contractor sectors, it is subservient to the monoliths of ASN and TyCom. If Pioneer's forecasts for the industry prove to be anywhere near correct, then the watchword should be "survival."

Julian Rawle is senior market analyst at Pioneer Consulting (Boston).