Vast growth in capacity demand spurs Asian optical infrastructure

While still considered a lag market compared with other global telecom markets, Asia presents solid opportunities now and in the future.

By ANNE LeBOUTILLIER and JOHN MANOCK,

T Soja & Associates Inc.

The telecommunications market in Asia has been characterized in the recent past by extensive deregulation and liberalization. These efforts have been largely in response to global pressure among governments and financial institutions to establish a competitive environment. The results have been staggering in terms of benefits to consumers, who have witnessed incremental price drops along with gains in access, flexibility, and choice in services. Although Asia has been a "lag" market in comparison to markets in Europe, the United States, and Latin America, the resulting growth in telecommunications and demand for bandwidth has been solid.

Combine the liberalization efforts with the Internet market, voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) and emerging bandwidth-intensive applications, and the Asian market emerges with huge potential in upcoming years. As with liberalization, Asia-Pacific lagged slightly in its acceptance and adoption of Internet technology-due mainly to the lack of existing Internet hosts (computers) in the region-and still suffers to some extent. But the region has demonstrated solid and continued growth rates in both Internet usage and Internet hosts in a trend that will undoubtedly continue. Additionally, Asia has been a leader in early adoption of second- and third-generation cellular technology and other such applications that will continue to drive the need for bandwidth on domestic, regional, and global levels.

How do these market trends affect the demand for undersea fiber-optic cable systems? While the Internet and its associated applications provide for huge demand and high-bandwidth allocation in the region, deregulation has contributed, as well, by bringing a number of new customers to the fiber-optic market. Systems are now being built in the region as strategic investments, where privately planned and funded undersea cable projects-with a variety of owners and shifting owner characteristics-have become the norm for several reasons:

- Private and cooperatively planned systems with bank financing and return-on-investment (ROI) initiatives save on up-front capital outlays, while also ensuring solid design plans and business cases built to focus on demand and growth markets.

- Planning time frames become shorter due to the ability of system owners to work in tandem or join existing system planners.

- Costs for bandwidth are reduced and planning cycles shortened for service providers as a result of capacity on demand, allowing new carriers to avoid purchasing bandwidth from the incumbent competitors that once owned 100% of the existing capacity.

At the same time as liberalization and the emergence of the Internet in the region, system developers also contributed to the growth of the undersea fiber-optic market through technology improvements that warrant huge amounts of undersea capacity at significantly reduced cost in relation to capacity. (While start-to-finish cable system costs were increased due to the rather significant requirement for additional terminal station equipment, the amount of capacity per system was more greatly increased, resulting in a lower overall price/capacity.) With the advent of DWDM technology-which, in essence, allows huge amounts of bandwidth to be built into each cable system along with the ability to adjust usage upward over time-the concept of bandwidth on demand was brought to fruition. This technology has made investments in undersea fiber-optic systems a much more appealing thought, as it allows for a system purchaser to save on up-front development costs with the long-term ability to increase the bandwidth provided on the system through later investments.

The Asian market continues to produce more and new market players. In the past, consortiums built undersea cable systems that committed dollars based on a conservative estimate of voice traffic growth and controlled bandwidth outlays and pricing schemes. The resulting unmet demand was due to two factors: the inability of much of the population to pay high prices for telecom services and the frequent inattention on the part of the monopoly incumbents to new markets and upgrades in domestic connectivity that would subsequently build regional and global connectivity.

Today, thanks largely to deregulation and high expectations of continued demand and growth in Asia, we are seeing new submarine cable projects driven by nontraditional parties in nontraditional manners. These parties tend to fall into four categories:

- Private global infrastructure builders, already having scored successes in the previously opened U.S. and European markets, are moving into the Asia-Pacific region. Examples include Global Crossing's East Asia Crossing project and the Tiger/FNAL cable being jointly constructed by Level 3 Communications and FLAG Telecom.

- New private infrastructure builders are emerging, either regionally focused in Asia-Pacific or starting there and planning to move into other areas later. The first example we have seen of this group is Nava Networks, which is building a private system between Singapore, Indonesia, and Australia.

- Traditional monopoly carriers are moving outside of their domestic territories in response to competition at home and becoming competitive carriers in neighboring countries. In Asia, SingTel is the most notable example of this group, building the regional C2C network on a private (versus consortium) basis and creating partnerships in India and Indonesia.

- New common carriers need to build their own infrastructure to avoid paying huge lease fees to their competitor, the former monopoly. These new players sometimes partner with a former monopoly in another country or with other new players in the region.

There is so much activity in the last group-"new common carriers" (NCCs) that were born of deregulation-it is worth looking at them in some detail. Examples of NCCs partnering with former monopolies are India's Bharti Telecom and SingTel for an India-Singapore cable and the Philippines' Globe Telecom and Taiwan's New Century Infocomm joining SingTel in C2C. The most unusual alliance, perhaps, is the partnership between SingTel and Indonesia's PT Telkom, two former monopolies joining to build a private international cable that falls outside Telkom's current market. In this case, Telkom, a monopoly in Indonesia's domestic market, is an NCC in an international project.

The prime example of new carriers joining together to build cables is the recently announced India-Malaysia-Singapore system. Although the details were not finalized at press time, the system is being pushed entirely by NCCs in the three countries-none of which has any previous submarine-cable building experience.

A smaller subset of this group is also worth mentioning. In countries where the geography supports them, NCCs are building domestic submarine systems. The first one of note in the Asia-Pacific region was built by Time dotCom in Malaysia in 1995. The carrier built a 1,600-km festoon around the Malaysian Peninsula. Although until recently, the company was better known for its financial travails, the submarine network remained one of its greatest assets.

Another major domestic system in the region was completed in 1998 in the Philippines. This was a 1,300-km network built by a consortium of NCCs known as Telic Phil. Since none of the new players had the financial strength to build a network alone, they joined together to build a nationwide backbone to compete with PLDT.

In 1999, a domestic system with an interesting heritage entered service-the 10,000-km Japan Information Highway built by KDD. In this instance, we had a former monopoly international carrier, KDD, building a submarine network to compete in the domestic market as an NCC. Since then, KDD has merged with alternative domestic carrier, DDI, and mobile operator, IDO, to create KDDI, a carrier that competes in all aspects of the market in Japan.

The latest domestic system to be announced by an NCC is in New Zealand. A new player, Telstra Saturn, plans to build an 800-km submarine system linking the country's major cities by the end of this year. Telstra Saturn is a partnership between Australia's former monopoly, Telstra, and New Zealand cable-television operator Saturn.

With the Asia-Pacific region boasting vast island nations like Japan, Indonesia, and the Philippines, as well as countries with huge coastlines, such as China, Vietnam, Malaysia, India, and Thailand, there is the potential for more domestic submarine systems as markets continue to open and new players continue to emerge. One common characteristic we find among all system purchasers is a business plan based on opportunity and growth markets.

In a market where ROI is now the overriding focus, system design is performed based on one of three factors: locations of unmet demand, such as the India market; locations of huge market growth, such as the China and Japan markets; and locations where domestic and regional connectivity are required to address the globalization of networks. There continue to be market opportunities in Asia that address all these factors.

There has been a significant emergence of planned regional and transpacific fiber-optic systems in the Asian market today. In fact, taking 1999 as the "changeover date" when privatization and competition began taking hold in the region, to say that the increase in activity is dramatic is a distinct understatement.

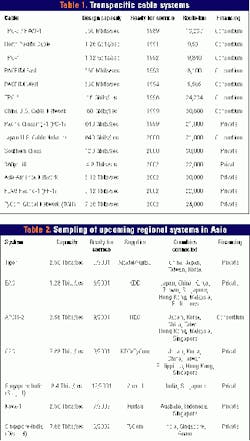

In the 10 years that followed the completion of the first transpacific fiber-cable in 1989, six transpacific systems totaling 70,000 route-km entered service. (Our definition of transpacific systems includes Australia-U.S. systems such as PacRim and Southern Cross.) In the four-year period 1999-2002, at least eight systems stretching 170,000 route-km are expected to enter service. Further, since all post-1998 systems use a ring configuration to provide full redundancy (as a protection for the high-capacity DWDM technology), more than twice as many cables (16 versus seven) will enter service under the Pacific Ocean in a four-year period than in the previous 10 years (see Table 1).Considering capacity on the transpacific route, the increase is nearly beyond comprehension. In the 10-year period from 1989 to 1998, the total capacity of the six transpacific systems in service amounted to about 9 Gbits/sec. The eight systems that will enter service between 1999 and 2002 will have a combined capacity of more than 24,000 Gbits/sec. In fact, it's worth noting that the process we use in rounding amounts of capacity results in a "drop-off" of about 200 Gbits/sec, which amounts to 20 times the total amount of capacity that entered service in the previous 10 years being discounted in the rounding process.

A similar situation to the transpacific market can be seen in the growth of regional systems (see Table 2). From 1989 to 1998, 15 international submarine cables entered service in the Asia-Pacific region, representing 46,000 km of cable. From 1999 to 2002, more than 17 systems (most likely a conservative estimate), covering more than 128,000 route-km, are likely to enter service. There are additional systems, many with solid business plans and reasonable demand forecasts, under discussion at this time. Since regional systems require a shorter lead-time to build than transpacific cables, it is possible there will be systems within the four-year time frame that have yet to be announced. As stated, the focus throughout the region continues to be on global connectivity, and both domestic and regional infrastructures are logical methods by which to ensure globalization.

Again, as with the transpacific market, growth in capacity is immense. The first 15 regional systems to go into service totaled about 17 Gbits/sec of capacity. The next group of systems will provide more than 60,000 Gbits/sec, or 3,500 times the amount of capacity installed from 1989 to 1998.

The change from consortium to private cable systems has been dramatic in Asia, as well. Regarding transpacific cables, only one of the six systems installed from 1989 to 1998 was a private system, North Pacific Cable (1991), which actually had many more characteristics of a consortium system than those seen today. By comparison, of the eight new systems entering service from 1999 to 2002, six are privately funded. The remaining two, China-United States and Japan-U.S., have employed some features of privately financed systems.

Similarly for regional projects, all 15 systems installed from 1989 to 1998 were by consortiums. For the 17 systems anticipated between 1999 and 2002, only five are consortium projects. Again, it is high-growth markets (markets with unmet demand and markets that do not currently have global access) that are the focal points in the region.

One of the concerns voiced in the Asian marketplace recently is that of too many systems being planned and designed with similar landing points, therefore, logically addressing similar markets. Indeed, there are distinct market advantages to being the first investor to open access to unaddressed markets-India being a prime example where several firms are vying for position. However, when it comes to financing, and in spite of recent hesitation within the financial community, there remain significant sums of cash being invested into projects within like markets. Indeed, while being first to market is always an advantage, in a market such as India and China (to name just two), where unmet demand is significant and available access is limited, there remain significant opportunities for follow-on systems.

Frequently, distinctly competitive strategies will gain the approval and interest of the investment community, which is what we see occurring in Asia. Further, as we've now stressed, the push to address the Internet, VoIP, and third-generation cellular technologies (with access to Web-based content), all require domestic (city-to-city), regional, and global connectivity to respond to consumer demands.

In Asia and throughout the world, as the consumer becomes smarter and more technically adept, his demands for connectivity and bandwidth availability become more urgent. In the Asian market of early adapters and technically sound consumers, newly competitive carriers are determined to address their customer requirements and respond fully to consumer needs. Without the ability to provide access and bandwidth, their business plans, strategies, and profitability measures are for naught. As a result, we will continue to see major build-outs in the region well into the future.

Anne LeBoutillier is director for the Asia-Pacific Singapore office and John Manock is director of information services at T Soja & Associates Inc. (Newton, MA).