Israeli entrepreneurs go optical

The market downturn hasn't stopped several Israeli startups from chasing the optical dream.

BY DAVID GREENFIELD

When 16-year old Doron Nevo babysat for Rami Oron, he could never have imagined it would lead to something bigger. Yet 30 years later, Nevo, Oron (now Dr. Oron), and Oron's father, Dr. Moshe Oron, are chumming around at a company called Kilolambda, developing a DWDM system that will yield nearly 1,000 wavelengths per fiber.

More wavelengths mean, of course, that fewer fibers need to be laid. It also means that large-scale wavelength services in the metro can become a reality. An immediate reality? Hardly. Yet over the long term, technologies like Kilolambda's could become key to unlocking the metro, says Stephane Teral, director of European optical transport at consultancy RHK Inc.

That kind of future-thinking seems almost commonplace here in the Israeli optical industry. Though set some 20,000 mi away from Silicon Valley, Israel has managed to produce its own version of the high-tech wonderland. The Internet revolution, biotechnology, and, yes, optics are being churned out of this tiny country of just 6.4 million people. Today, there are some 50 optical startups around Israel. On a per-capita basis, that would equate to about 2,200 optical companies within the United States.

Three major factors drive this growth: an inherent entrepreneurial attitude bred in Israel, world-class research universities, and funding through the venture capital community. The result has been a set of research-intensive companies that give a glimpse of how optical systems may be shaped over the next few years. The ultimate hope of many is to produce the thing that's eluded so many Israeli entrepreneurs-an Israeli-based optical powerhouse.

Perhaps no company better exemplifies the highs and lows of the Israeli optical industry than Chromatis. Lucent Technologies' purchase of the metro optical manufacturer in 2000 for $4.7 billion ignited the Israeli industry. "Chromatis became a benchmark for entrepreneurs by which to measure their success, says Adam Fisher, a principal in Jerusalem Venture Partners, a venture capital firm and seed investor in Chromatis, "It wasn't uncommon to hear entrepreneurs aspire to be the 'next Chromatis.'"

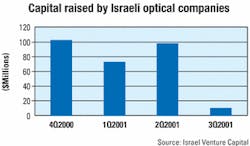

All of that ended last summer, when Lucent closed the former startup here. "It's instilled a sense of sobriety in the optical community here that's been lacking," says Fisher. Unfortunately, he expects more of the same over the next six months from other startups. Not surprisingly, investment in optical communications has fallen significantly since a year ago (see Figure 1); unemployment is up and the government has officially declared a recession. In short, optical companies are rolling back business plans and waiting out the storm or, like Chromatis, they are closing.Yet despite the near-term gloom and doom, the optical market here has all of the key ingredients for long-term growth-research and development, funding, and experience. Little wonder that in a report last May, Morgan Stanley Research predicted that global optical companies would turn to Israel as a major source of acquisitions. Even after the optical market crash, Morgan Stanley continues to expect Israel to provide fertile ground for acquisitions.

Nor are the current political problems posing a challenge for this technology hotbed. The situation might give buyers and investors some pause, but the impact on business is "negligible to nonexistent," says Dr. Eyal Shekel, founder, vice president, and general manager of Chiaro (pronounced key-ah-roe) Networks, an optical-switch and high-end-router manufacturer.

That might be because history has shown the productivity of Israeli companies is relatively immune to regional politics. "Customers were very much astonished that it was business as usual during the Gulf War, so now they know that nothing stops us," says Menachem Kaplan, chief technology officer at Native Networks, a network access equipment manufacturer (see Lightwave, January 2001, page 66, and June 2001, page 108). "Yeah, we had missiles falling at night, but so what? We work."

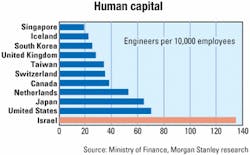

While the archetype of the gun-toting Israeli farmer with hoe in hand protecting his country and kin may have inspired a generation, today it's the engineer turned entrepreneur with laptop in tow. It's little surprise then that there are more engineers per capita in Israel than anywhere else in the world. Israel, for example, has about 140 engineers per 10,000 employees versus the roughly 70 engineers within the United States (see Figure 2).

Many of those engineers and doctoral students are doing their research in Israel's world-class universities. Israel has been able to develop renowned research institutions like the Technion, Ben Gurion University, and Tel Aviv University. Homegrown talent is particularly important because of the strong connection between optical research and commercial optical products.

University research has already propelled a number of startups. Trellis Photonics, an optical-switch manufacturer, for example, uses electro-holography in its switch designs (see Lightwave, December 2000, page 70), technology developed from research done by Aharon Agranot at Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Down in Beersheva, Ben Gurion University is home of Dr. Dan Sadot, who splits his time between teaching at Ben Gurion and being the chief technology officer of XLight, a startup in Tel Aviv developing a subsystem that can rapidly tune multisectional lasers for use in a DWDM system. Multisectional lasers, like Agility's SSG-DBR, provide a wide tuning range of more than 35 nm. Single-section DBR lasers, by contrast, hold a tuning range of just 10 nm or less.Like conventional lasers, multisectional lasers consist of an active cavity within which the lasing effect occurs. Instead of the typical reflective surface at either end of the cavity, however, these lasers incorporate several independent grating sections, where the grating structure is more complex. The light built up in the cavity is passed through these gratings, whose particular characteristics enable a specific frequency to be generated. By passing current across the grating, the grating's reflective index changes, altering the light's characteristics.

The problem, says Sadot in an e-mail, is that there are billions of possible combinations of currents that can be used to generate a particular wavelength. What's more, the light must be stabilized so its frequency doesn't shift under ultra-fast dynamic conditions. At the same time, the shape of the current must be optimized. And all of that must be done while meeting very high electrical accuracy, stability, and isolation requirements.

"It's a three-dimensional problem like flying a plane," says Sadot, an ex-cadet in the Israeli air force. "The pilot doesn't even appear to be doing anything, just slightly moving the stick, but the big deal is knowing when to move the stick to a particular position. It's the same thing with tuning a laser. It's not knowing how to apply current to yield a particular frequency, but which current to apply and when that's so important."

Sadot says that his team has been able to arrive at a solution for tuning lasers to particular frequencies within 50 nsec. By contrast, vendors like Agility tout their ability to tune lasers within 10 msec-a million times slower.

Part of Sadot's work will face serious competition. Marconi claims its Digital Supermode DBR (DS-DBR) laser can be calibrated with a single voltage as opposed to the multiple voltages required with other multisectional lasers, eliminating one of the major breakthroughs of Sadot's work. Yet, the young professor isn't too worried about Marconi. "It will make part of the tasks easier indeed," he admits. "Still, we do have a lot of value added in operating these lasers, and we have tight contacts with their relevant group."

Across town, another professor turned entrepreneur, Dr. David Mendlovic of Tel Aviv University, is explaining the origins of his company, Civcom, a startup specializing in all-optical switching (see Lightwave, November 2001, page 92). Mendlovic says that Civcom was actually the first optical startup to be spun out of Tel Aviv University.

"Our process was very unique at the time where we first transferred patents from the university. It was a process that included President Itamar Rabinovich [the former Israeli ambassador to the United States] and various other high-level positions," he says, "The deal with the university gives us the ownership on the patent and my freedom and in return a part of the company."

The company has developed two core technologies. Civcom's Free-X line of optical switches provides switching using free-space propagation and polarization encoding of optical signals. The result, claims Jacob Vertman, vice president of business development at Civcom, is that the company enables ultra-fast, polarization-independent, strictly nonblocking switching. Initially, Civcom is introducing 1x2 and 2x2 switches with switching times of about 200 nsec.

Aside from the blazing fast switching speeds, Vertman is quick to point out three other benefits to the Free-X switches. All of them integrate variable-optical-attenuator (VOA) functionality. The VOA is needed to reduce and normalize the power of incoming light, thus preventing problems such as crosstalk. The switch also has no moving parts, so wear and tear is nominal. Finally, the switch will support multicasting so one optical port can direct output to several other optical ports.

The second core technology is what the company calls its Cobra Wave Processing technology. Civcom is pretty tightlipped when it comes to Cobra; all Vertman would say is that it combines switching and filtering in a variety of applications.

The dark horse in Israel might be a lesser-known institution, Jerusalem College of Technology, a science college in Jerusalem catering to orthodox Jews. "You don't see them much because they aren't driven to run companies," says Moshe Oren. "They're driven to learn the Torah [bible], but look in any startup and you'll find engineers from Machon Lev [the colloquial name for the institution]."

Perhaps the most prominent optical graduate of Machon Lev is Chiaro's Shekel. According to Shekel, the inefficiencies in today's public network stem from its hierarchical architecture. There's an aggregation layer of switches that gathers the access lines, then there's the core of the network. The problem, says Shekel, is that 70% of the line cards between the two layers are used just to talk with one another in the central office. That's a huge waste of capital resources. With so many switches in the network, there's also more of a likelihood of a failure.

His answer is to develop a massive optical switch with enough aggregate capacity to handle hundreds of line cards that may not be even be located in the same unit or building. The switch is an optical phased-array device based on gallium arsenide that will rely on the electro-optical effect to switch light. Shekel says that Chiaro will disclose the exact details at next month's OFC 2002. All that he will say is that Chiaro is producing 64x64 switching elements that will enable up to 315x315 OC-192s to be switched in milliseconds.

What makes Shekel's efforts particularly unusual is that unlike many current optical startups, Chiaro is producing an entire system. Most new optical companies are looking to leverage the R&D skills of Israel to develop components or subsystems.

That wasn't always the case. ECI Telecom and Tadiran (acquired by ECI in 1999) were large Israeli telecommunications equipment companies. ECI's expertise in SDH led it to become a leading supplier of SDH gear in Europe. ECI also created one of the world's first optical rings in 1999 for the local telephone company, Bezeq, according to Ido Gur, vice president of marketing at Lightscape Networks, formerly the optical division of ECI and currently a supplier of SDH/SONET gear. Today, entrepreneurs increasingly conclude that systems manufacturers don't necessarily play fully into Israel's perceived core competencies. Carriers currently are less willing to risk their networks on a startup than they might have been a year ago-particularly a startup that might be long on R&D but short on marketing and selling to a traditional telco. For a carrier to purchase a system from an Israeli startup takes "some guts," says Nevo.

Ron Shilon certainly knows what Nevo is talking about. The CEO of Flexlight Networks, a supplier of passive-optical-network (PON) subsystems, is giving the company's pitch as we sit in the mall in Petach Tikva. Shilon has a simple explanation of why Flexlight is going after the subsystem market. "It's just too difficult for small startups, located 10,000 mi away, to pitch the carriers directly," he says. Instead, Flexlight's technology will be available to PON suppliers for integration into their own equipment or as a blade for integration directly into the metro gear.

Shilon's PON solution is unique. Most PONs carry either ATM traffic, in the case of ATM PONs (APONs), or Ethernet traffic, in the case of EPONs, without requiring any active components between the switching center and subscriber. By avoiding having to power components in the fiber infrastructure, PONs can more than halve the cost of deploying fiber access.

However, there are problems with both approaches. The full cost reductions have not been realized with ATM. ATM gear is still quite expensive compared to Ethernet products. Performance is limited due to the segmentation and reassembly needed when dividing packets into ATM's 53-byte cells. What's more, the ATM cell tax wastes bandwidth. The combination of these factors plus other limitations of ATM PONs, such as low speeds and lack of multicast support per service, have led to Ethernet PONs.

Yet, Ethernet PONs carry their own limitations. Ethernet doesn't yet provide built-in quality of service (QoS) to ensure the delivery of toll-quality voice and high-resolution video. MPLS, differentiated services, and other mechanisms can be layered on top of Ethernet to provide these services, but only with higher cost and complexity. There also is no operations, administration, maintenance, and provisioning (OAM&P) functionality in Ethernet, which limits the performance monitoring that a carrier can provide in the network.

Flexlight has instead developed what it calls Multiprotocol PON (MPL-PON). MPL-PON uses a proprietary algorithm that enables any two ends to a protocol-pipe to be connected together over a public network in their native formats. No complex conversions are required for circuit-switched voice or Ethernet data. MPL-PON, like APON or EPON, is built along a synchronous network where a certain number of time slots are allocated and reallocated to each type of data according to the defined service-level agreement. Through dynamic bandwidth allocation, time slots can be reallocated on the fly. OAM&P functionality is built into the protocol.

Over the long term, prospects for the Israeli optical industry are as rosy as anywhere. A recent change in Israeli tax law should free U.S. investors from being doubly taxed on Israeli investment. Over the long term the tax change should help increase foreign investment.

What that investment will go toward is the question for many. One forward thinker is Zohar Zissapel. The chairman of RAD Data Communications, a producer of edge telecom and datacom equipment, Zissapel also is the co-owner of the successful RAD Group (split with his brother, Yehuda Zissapel). The group doesn't have a specific play in the optical space. The nearest foray, RADOp-a venture that was supposed to yield a collaboration between RAD and academic research-never really took off.

Yet, Zissapel's influence within the industry here and his ability to have produced arguably more Israeli startups than any other entrepreneur in Israel give him a unique view on the market. And his biggest worry right now? There aren't enough startups.

"We had too many startups two to three years ago," he says. Now, those startups are all "teenagers with all of the problems of teenagers" chasing after a market that has disappeared and consequently looking to raise money, lots of money, at a time when getting capital isn't easy.

Today, however, he says very few entrepreneurs are brave enough to open a company. In three to four years, "we'll have middle-aged companies but no up-and-coming stars."

And if past record is any indication of the future, many of the companies will look to cash out early, a problem that Tzvi Marom, president and CEO of BATM, a manufacturer of optical switches, laments. "We have not been able to build an optical industry here as much as we've built a collection of individual companies," says Marom, "Behind someone who sells products from Japan, for example, are zillions of companies supporting them." In Israel, Marom says that entrepreneurs have become so infatuated with the fast exit that there is no opportunity to craft those kinds of larger companies.

Instead, Israel has become a sort of startup production line, generating high-tech startups that are subsequently acquired by the Nortels, Ciscos, and Lucents of the world. Then again that may not be such a bad position after all.

David Greenfield is the international technology editor for Network Magazine, where he tracks optical technologies, and is the author of The Essential Guide to Optical Networking, published by Prentice Hall. He's currently based in Jerusalem and can be reached at [email protected]. The author wishes to thank several people who helped provide background and insight into the Israeli optical industry, including Yossi Boker of Red-C Optical Networking, Aaron Mankovski of Pitango Venture Capital, Erel Margalit of Jerusalem Venture Partners, and Yaki Luzon of PacketLight Networks.