Fiber cabinets protect and connect

by Meghan Fuller Hanna

They may be easy to dismiss as simple metal boxes that clutter our neighborhoods and crowd our curbsides, but today's fiber cabinets provide much more than just shelter for telecom equipment. "In a sense it's a metal box, but at the same time, it's a lot more than that," says Lindsay Allen, director of product management at CommScope (www.commscope.com). "We are in the business of protecting and connecting carrier-grade networks."In the past, all telecom (i.e., telephone) equipment was housed in a well-protected central office; only the copper cables were located in the outside plant. But with the advent of broadband networks—both fiber-to-the-home (FTTH) and fiber-to-the-curb/node (FTTC/N)-based architectures—comes the need to locate more equipment in the outside plant.

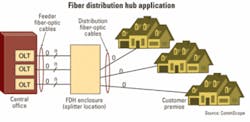

In the case of an FTTH network, the fiber cabinet or fiber distribution hub (FDH), as it is sometimes called, provides an interconnection point between feeder fiber, which comes from the central office, headend, or content origination point, and distribution fiber, which runs downstream from the cabinet to the customer premises (see figure).

Fiber cabinets for EPON/GPON networks feature planar lightwave circuit (PLC)-based optical splitters, while cabinets that support active Ethernet networks can act as passive crossconnects.

In reality, then, the cabinet manufacturer must consider everything from fiber management to environmental robustness to technician usability, says George Wakileh, director of outside plant products in the Energy Systems Business Division of Emerson Network Power (www.emerson.com). Consider a 288-port cabinet in a GPON network. That cabinet would support 288 fibers on the distribution side and on the feeder side up to nine optical splitters, each supporting 32 customers.

"What do you do with all those jumpers?" Wakileh asks. "How do you manage them? Can the technician go in there and intuitively route jumpers? Can they intuitively identify a circuit without disturbing the circuits around it? How quickly can they deploy [the cabinet]? How quickly can they maintain it? What is the cost of ownership?"

Several standards bodies, including Telcordia and the USDA's Rural Utilities Service (RUS), have developed specifications for fiber cabinets and enclosures, but because environmental and thermal protection are so critical, it's important for manufacturers "to develop their own internal standards based on the environment they are in," notes Johnny Hill, vice president of engineering and product management at Clearfield Inc. (www.clearfieldconnection.com).

The folks at Clearfield, which is based in northern Minnesota, know first-hand how robust an outdoor fiber cabinet has to be. Here, it is not unusual to experience 60° temperature swings in a 12-hour period, says Hill. "We often have 20°- to 30°-below temperatures, so while Telcordia will say a riser-rated jacket meets performance standards at cold temperatures, the cable itself is very stiff at that temperature," he confirms. "We use a material that remains flexible even at 40° below and resists sagging at extremely high temperatures."

Generally speaking, the smaller the cabinet, the better for all parties involved—from the installers and technicians to the carriers and even the end users. From an aesthetic point of view, people simply don't like to see large cabinets cluttering up their neighborhoods. In fact, says Allen, some cities, like Los Angeles, restrict how large these structures can be. In L.A., "they can't be higher than 48 inches tall, and the total cubic volume of the cabinet and the power pedestal has to be less than 36 cubic feet. So you're talking about 6 ft Ã� 6 ft Ã� 0 or 3 ft Ã� 3 ft Ã� 4 ft. The smaller they are, the better they are for the neighborhoods."For this reason and also because carriers in urban areas are simply running out of real estate, fiber cabinet manufacturers say they are under pressure to pack more fiber into the same size or a smaller cabinet than those that are available today. One way to achieve higher density within the cabinet is to use either a smaller connector or a multi-fiber ribbon cable. Today's outdoor cabinets typically employ individual fiber to individual fiber connections via flat or angle-polished SC to SC couplers.

By contrast, two LC connectors can fit into the same space as a single SC connector; an MTP connector fits into roughly the same footprint as an SC connector and supports a ribbon of four, eight, or twelve fibers versus a single fiber in the SC configuration.

"But you have to be careful with that," cautions Hill, "because single-circuit access is important in fiber to the home from a testing perspective and everything else. If you've got an MTP connector that has 12 channels of traffic on it and you have a problem with one of those, you have to take down 11 other customers to troubleshoot it."

That said, all sources interviewed for this story believe the MTP connector-based cabinet is coming. They are quick to note that there is nothing technically challenging from a cabinet perspective; it's a coupler design issue that prevents the use of MTPs in outdoor cabinets today. Couplers that can achieve MTP-to-MTP splitting have yet to be developed.

The MTP connector-based cabinet may prove especially beneficial in multi-dwelling unit (MDU)-type applications where there is sometimes uncertainty about which carrier or provider owns the existing copper infrastructure within the building. In such cases, the broadband provider cannot use the copper to deliver service from an MDU ONT out to individual tenants within the MDU. Instead, says Allen, "they are going fiber to a single-user ONT, and that's causing this combination fiber distribution hub cabinet that comes in with ribbon cable and goes out with single-fiber SC connectors. This is not as efficient in terms of space," he notes, "And it's a lot more costly to make that type of connection. The next thing coming down is this MT-to-MT-type coupler in a fiber distribution hub cabinet."

While tomorrow's cabinets will no doubt be smaller in size, they will also have to be far more flexible. Wakileh confirms that Emerson Network Power is currently working on a cabinet that is topology-agnostic, enabling service providers to support any access network topology from the same cabinet. In other words, he says, "Can you take a cabinet that is currently capable of doing GPON and make it an active optical network cabinet? Can you upgrade it to a CWDM- or WDM-PON architecture?"

Emerson envisions a modular design in which one module could be added to make the cabinet a crossconnect for an active Ethernet application, while another module—a splitter module—could be used to equip that same cabinet for an EPON/GPON application.

"Good plug-and-play, low install costs, quick time to market, topology-agnostic: All these things are going to change the way service providers deploy [cabinets]," says Wakileh, "and that's where we're heading in the future."

For his part, Clearfield's Hill also predicts a move toward greater automation in the cabinet. "As we get further out, the need to manually connect a customer could be replaced in larger networks with digital fiber switches or crossconnects where, from the central office, you are doing your allocation to the subscriber when they call up for service," he says. "From an opex standpoint, I think you're going to see those dollars really drop because fiber is much easier to maintain and build than a copper network."

That said, Hill also cautions that all the "extra bells and whistles," as he calls them, shouldn't overshadow the overall mission of the fiber cabinet. "If you just follow the four basic rules of fiber management—good access, bend-radius protection, physical fiber protection, and route paths that protect the fibers as these route in and out of the cabinet—you are most likely going to end up with a good product," he says. "Ultimately, the customer is paying for that."

Meghan Fuller Hanna is senior editor at Lightwave.