Diamond-like film-encapsulated fibers enable long-length grating production

Moses M. David and James F. Brennan, III 3M

Several researchers have been perfecting the fabrication of fiber Bragg gratings that are several meters in length.1-3 The application of these devices in optical telecommunications systems is imminent. A great deal of theoretical and experimental work has been done to understand the optical performance of these devices, but until recently, little attention has been given to maintaining the mechanical integrity of the gratings. Before they are seriously considered for use in communications systems, long fiber gratings must pass rigorous mechanical reliability tests and be easily manufactured.

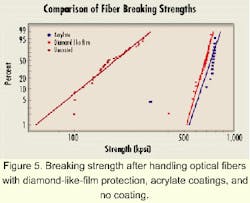

In standard fiber Bragg grating production, the protective coating on a fiber must be removed before a grating can be written. Afterward, the fiber is immediately recoated to preserve its mechanical strength. The process of stripping and recoating a fiber is time-consuming and tedious, requiring skilled technicians. Additionally, the bare fiber is prone to damage during grating inscription, which reduces production yields. These problems are exacerbated when long lengths of fiber are stripped, handled, and recoated.

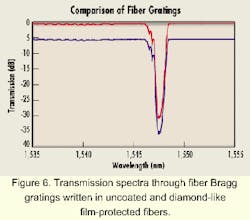

Several solutions have been proposed to eliminate these process steps. Most of the solutions involve writing gratings through specialized, UV-transparent polymeric fiber coatings.4-6 Writing gratings through a fiber coating may be a solution for short-length (less than a few centimeters) fiber Bragg grating production, but to be used in long-length grating production, a write-through coating must meet demanding physical and optical requirements.7

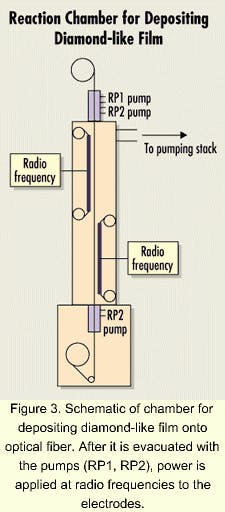

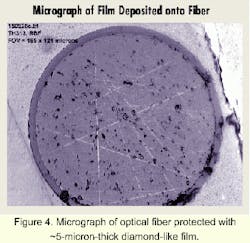

A process has recently been developed to deposit a UV-transparent, diamond-like film onto fiber to maintain the mechanical integrity of the fiber close to that of pristine fiber. By depositing a thin film on the fiber (~1-5 microns thick), fiber geometry such as concentricity and diameter is preserved to the degree necessary to produce long fiber Bragg gratings. This diamond-like film can also withstand the temperatures used to anneal fiber gratings.

Carbon films contain substantially two types of carbon-carbon bonds: trigonal graphite bonds (sp2) and tetrahedral diamond bonds (sp3). Diamond is composed almost entirely of tetrahedral bonds; diamond-like film, approximately 50% to 90% tetrahedral bonds; and graphite, nearly all trigonal bonds. The crystallinity and nature of the bonding of the carbon network can be manipulated to affect the physical and chemical properties of a diamond-like film. Diamond is crystalline and essentially pure carbon, whereas diamond-like film is amorphous and can contain a substantial amount of additional components.The composition of diamond-like films can be tailored so they have desirable diamond-like optical and mechanical properties such as extreme hardness (1,000 to 2,000 kg/mm2 Vickers). Diamond's optical bandgap is 5.56 eV (~223 nm) and is therefore transmissive in the ultraviolet, but the polycrystalline structure of diamond films causes light scattering from grain boundaries. Diamond-like films are amorphous and don't suffer from light scattering at grain boundaries. The carbon-carbon double-bonding prevalent in diamond-like film causes undesirable optical absorption below ~500 nm.

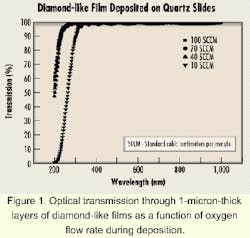

By incorporating silicon and oxygen atoms into the amorphous diamond-like carbon film during the deposition process, absorption is altered. For example, diamond-like film of 1 micron thick was deposited on quartz slides as the oxygen flow rate during deposition was varied, and the optical transmissions through these slides were measured (see Figure 1).In the visible wavelength region, the optical transmission is close to 100% for all diamond-like films, irrespective of the chemistry. In the UV region, diamond-like films' transmission drops dramatically when the oxygen flow falls below 10 sccm (standard cubic centimeters per minute). The optical transmission of the 10-sccm film drops below 30% at 244 nm, a commonly used wavelength for writing Bragg gratings. Under certain deposition conditions, a 1-micron-thick layer of diamond-like film is ~98% transmissive at 244 nm. The oscillations in the transmission spectra are due to thin-film interference.

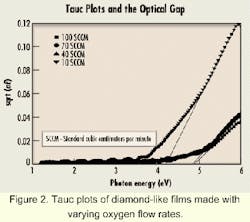

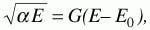

The electronic-absorption edges in diamond-like films follow the Tauc relation:These findings present significant opportunity for the fabrication of long-length fiber Bragg gratings that lend themselves to high-yield manufacturing processes. Critical to the process is this UV-transparent film, which protects the fiber during fiber grating inscription and maintains the geometry of the fiber during fabrication.

By developing a process to deposit a uniform layer of diamond-like film onto optical fibers, many of the major process and handling obstacles have been overcome. This significant new process opens up opportunity for further applications of longer-length fiber Bragg gratings throughout the optical network.

- H. Rourke, et al., BGPP '99, ThD1.

- J. Brennan and D. LaBrake, BGPP '99, ThD2.

- L. Garrett, et al., OFC '99, PD15.

- R. Espindola, et al., OFC '97, PD4.

- K. Imamura, et al., Electron. Lett., 1998, 34 (10), 1016-7.

- L. Chao and L. Reekie, OFC '99, ThD5.

- M. Ibsen and R Laming, OFC '99, FA1.

- J. Mort and F. Jansen, "Plasma Deposited Thin Films" (CRC Press, Boca Raton, 1986), 111-4.

Moses David, Ph.D., is an advanced research specialist at 3M (St. Paul, MN), where he specializes in plasma processing, diamond-like films, and thin-film optics. James F. Brennan, III, Ph.D., is a research specialist for 3M Telecom Systems Division (Austin, TX), where he works on the fabrication of long-length gratings for dispersion compensation.