Newly formed mega-companies face scrutiny among analysts

Consolidation in the optical components industry is shining the spotlight on newly formed mega-companies such as Avanex (Fremont, CA). Yet, is a huge product line too great a burden to bear in a depressed optical-component market? A survey of analysts reveals differing views on this "bigger is better" strategy.

In May, Avanex announced its plans to acquire Alcatel Optronics and parts of Corning's photonics business, in combined transactions valued at about $63.5 million, based on Avanex's closing price of $1.12 per share on May 9. Part of the deal is a three-year supply agreement with Alcatel's optical-networking division. The deal is expected to be finalized by the end of next month, pending regulatory and shareholder approvals.

Avanex significantly expanded its product line with the acquisitions, adding arrayed-waveguide gratings, fiber Bragg gratings, lasers, optical amplifiers, photodetectors, receivers, transponders—all from Alcatel—and dispersion compensation modules, electro-absorption modulators, lithium niobate modulators, micro-optic products, and optical amplifiers from Corning. When the transactions close, there will be some product overlap (optical amplifiers and dispersion compensation modules) and some holes, notably in low-data-rate telecommunications interface modules and data communications transceivers, according to research by RHK (South San Francisco).

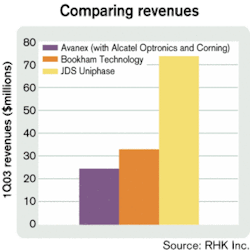

The deals put Avanex on the same path charted by JDS Uniphase (JDSU), Bookham Technologies, and potentially TriQuint, which purchased the optical-component portions of what used to be Lucent Technologies' Microelectronics Division. The move is a good one, according to Daryl Inniss, program director for the optical components program at RHK. "[Avanex] had a product portfolio where it was going to be very difficult for them to grow revenues in the near-term, so it really gives them an opportunity to build a company that can perform in this market," surmises Inniss.

Avanex must work fast to successfully combine the three entities and build the new company, however. "The numbers kind of force that issue," says Inniss. "They have $250 million in cash and a $25-million burn rate, and they don't want that to decrease too much, so they have about a year to get the ship right."

There is no doubt that size has its advantages, according to Lawrence Gasman, president and director of optical components research at Communications Industry Researchers (CIR—Charlottesville, VA). "One of the things that got JDSU really zinging during the glory days of optics was, if you were a really small company or even a big one, you could go and get, if not quite one-stop shopping, very close to it, and that's very attractive," he explains. "First of all, it saves you time. Secondly, you can do deals easier, 'Give us 10¢ off the transponders and we'll give you a bit more on the VOAs [variable optical attenuators].'"

In the current market climate, customers are also understandably nervous about the longevity of suppliers. Larger companies appear more stable. "That is one of the things that is really driving consolidation," asserts Gasman. RHK analysts agree, stating in their report, "Avanex Joins the Giants in Optical Components," system vendors "will work with companies that are committed to this industry as demonstrated by their size, product portfolio, and balance sheet."

But believing that a handful of large mega-companies will become the dominant competitors in the optical-component market is somewhat shortsighted, according to Tom Hausken, director of the optical components practice at Strategies Unlimited (Mountain View, CA), a research unit of PennWell. "Alcatel's sales for the last quarter were 7 million euros, about $30 million a year, and Corning's were 11 million euros so that's $40 million a year, and that's less than some of these other companies like OCP or Finisar. So when you put it in that perspective, then these big giants aren't giants anymore—all bets are off."Asian component vendors should also not be counted out. "There's still a plethora of companies that are mushrooming in China and in Korea and in Tawain," says RHK's Inniss. "I would keep my eye on what's going on in the Far East and see if any of those companies start to develop into a significant player, because there are just so many that it makes you think that it is just an amount of time before they start to emerge."

How many broad-based companies can survive in what is now a $2- to $3-billion optical-component market? "It isn't going to be six, but it might be four or five, and three of them are fairly clear," says CIR's Gasman.

Will optical-component companies have to go out and form partnerships to broaden their product lines to compete with mega-players like JDSU, Bookham, and Avanex? Strategies Unlimited's Hausken doesn't think so: "If you look at automobiles or semiconductors or other businesses, you have companies that specialize in microprocessors or DSPs or brakepads or tires; you don't necessarily have companies that are one-stop shops for everything." RHK analysts, on the other hand, advise optical-component startups to form partnerships, stating in their recent report that it is "almost impossible to go it alone in this market."

Stephen Hardy contributed to this report.