CWDM: lower cost for more capacity in the short-haul

The opportunity to add two to eight wavelengths per fiber allows network designers to increase capacity without installing costly DWDM systems.

MARCUS NEBELING, Fiber Network Engineering

Coarse wavelength-division multiplexing (CWDM) technology was first commercially deployed in the early 1980s for transporting digital video signals over multimode fiber. Quante Corp. marketed a four-wavelength system that operated in the 800-nm window with four channels at 140 Mbits/sec. These systems were primarily used in cable-TV links. However, CWDM systems did not generate significant interest among service providers-until now.

As metro carriers seek cost-effective solutions to their transport needs, CWDM is becoming more widely accepted as an important transport architecture. Unlike DWDM, systems based on CWDM technology deploy uncooled distributed-feedback (DFB) lasers and wideband optical filters. These technologies provide several advantages to CWDM systems such as lower power dissipation, smaller size, and less cost. The commercial availability of CWDM systems offering these benefits makes the technology a viable alternative to DWDM systems for many metro and access applications.

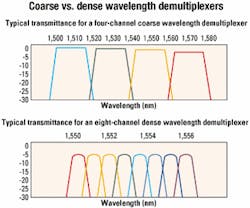

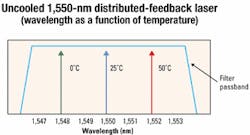

The bandwidth of a fiber-optic link can be increased by transmitting data faster or transmitting multiple wavelengths in a single fiber, known as WDM. WDM is accomplished by using a multiplexer to combine wavelengths traveling on different fibers into a single fiber. At the receiver end of the link, a demultiplexer separates the wavelengths and routes them into different fibers, which all terminate at separate receivers (see Figure 1). The spacings between the individual wavelengths transmitted through the same fiber serve as the basis for defining DWDM and CWDM (see Figure 2).DFB lasers are used as sources in DWDM systems. The laser wavelength drifts about 0.08 nm/°C with temperature. DFB lasers are cooled to stabilize the wavelength from drifting outside the passband of the multiplexer and demultiplexer filters as the temperature fluctuates in DWDM systems.

CWDM systems use DFB lasers that are not cooled. These systems typically operate from 0 to 70°C with the laser wavelength drifting about 6 nm over this range. This wavelength drift coupled with the variation in laser wavelength of up to ±3 nm due to laser die manufacturing processes, yields a total wavelength variation of about ±12 nm. The optical filter passband and laser channel spacing must be wide enough to accommodate the wavelength variation of the uncooled lasers in CWDM systems (see Figure 3). Channel spacing in these systems is typically 20 nm with channel bandwidth of 13 nm.

CWDM systems offer some key advantages over DWDM systems for applications that require channel counts on the order of 16 or less. These benefits include costs, power requirements, and size.

The cost difference between CWDM and DWDM systems can be attributed to hardware and operating costs. While DWDM lasers are more expensive than CWDM lasers, the cooled DFB lasers provide cost-effective solutions for long-haul transport and large metro rings requiring high capacity. In both of these applications, the cost of the DWDM systems is amortized over the large number of customers served by these systems. Metro-access networks, on the other hand, require lower-cost and lower-capacity systems to meet market requirements, which are based largely on what the customer is willing to pay for broadband services.The price of DWDM transceivers is typically four or five times more expensive than that of their CWDM counterparts. The higher DWDM transceiver costs are attributed to a number of factors related to the lasers. The manufacturing wavelength tolerance of a DWDM laser die compared to a CWDM die is a key factor. Typical wavelength tolerances for DWDM lasers are on the order of ±0.1 nm; whereas tolerances for CWDM laser die are ±2-3 nm. Lower die yields also drive up the costs of DWDM lasers relative to CWDM lasers. In addition, packaging DWDM laser die for temperature stabilization with a Peltier cooler and thermister in a butterfly package is more expensive than the uncooled CWDM coaxial laser packaging.

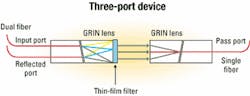

The cost difference between DWDM and the CWDM multiplexers and demultiplexers contributes to lower overall system costs in favor of CWDM as well. CWDM filters are inherently less expensive to make than DWDM filters due to the fewer number of layers in the filter designs. Typically, there are approximately 150 layers for 100-GHz filter designs used in DWDM systems, whereas there are approximately 50 layers in a 20-nm, CWDM filter. The result is higher manufacturing yields for CWDM filters. In the manufacture of CWDM three-port devices, the alignment tolerances are relaxed relative to those for DWDM devices so that the manufacturing costs for CWDM devices are significantly less (see Figure 4). The CWDM filter costs about 50% less than the DWDM filter and is projected to drop by a factor of three in the next two to three years as auto mated manufacturing takes hold. The adoption of new filter and multi plexing/demultiplexing technologies is expected to decrease costs even further.

The operating costs of optical transport systems depend on maintenance and power. While maintenance cost are as sumed to be acceptable for both CWDM and DWDM systems, the power requirements for DWDM are significantly higher. For example, DWDM lasers are temperature-stabilized with Peltier coolers integrated into their module package. The cooler along with associated monitor and control circuitry consumes around 4 W per wavelength. Meanwhile, an uncooled CWDM laser transmitter uses about 0.5 W of power. The optical transport section of a four-channel CWDM system consumes approximately 10-15 W of power, while the same functionality in a DWDM system can consume up to 30 W. As the number of wavelengths in DWDM systems increases-along with transmission speeds-power dissipation and the thermal management associated with it become a critical issue for board designers.The lower power requirement resulting from the use of un cooled lasers in CWDM systems has positive financial implications for system operators. For example, the cost of battery backup is a major consideration in the operation of transport equipment. Minimizing operating power and the costs associated with its backup, whether in a central office or a wiring closet, reduces operating costs.

CWDM lasers are significantly smaller than DWDM lasers. Uncooled lasers are typically constructed with a laser die and monitor photodiode mounted in a hermetically sealed metal container with a glass window. These containers are aligned with a fiber pigtail or an alignment sleeve that accepts a connector. The container plus sleeve forms a cylindrical package called a transmitter optical subassembly (TOSA). A typical TOSA is approximately 2 cm long and 0.5 cm in diameter. Cooled lasers are offered in either a butterfly or dual inline laser package and contain the laser die, monitor photodiode, thermister, and Peltier cooler. These lasers are about 4 cm long, 2 cm high, and 2 cm wide. These devices are almost always pigtailed, requiring fiber management, a heat-sink, and corresponding monitor and control circuitry. The size of a DWDM laser transmitter typically occupies about five times the volume of a CWDM transmitter, i.e., 100 cm2 (16 inches2) compared to a CWDM transmitter with an uncooled laser occupying 20 cm2 (3.5 inches2).

The reliability of DFB lasers used in DWDM and CWDM transport systems has been proved in both cooled and uncooled designs. The difference between the two laser designs is the number of additional components, including the Peltier cooler, thermister, and associated electronics in DWDM lasers. However, this author has no data to substantiate a significant reliability difference between the two types of systems in real world applications. Further analysis may or may not suggest otherwise.

CWDM systems supporting two to eight wavelengths are commercially available today. These systems are anticipated to scale to 16 wavelengths in the 1,290-1,610-nm spectrum in the future.

Today, most CWDM systems are based on 20-nm channel spacing from 1,470 to 1,610 nm, with some development occurring in the 1,300-nm window. Wave lengths in the 1,400-nm region suffer higher optical signal loss due to the attenuation peak caused by residual water present in most of the installed fiber today. While this additional loss can limit system performance for longer links, it is not an obstacle to CWDM deployment in most metro access spans.

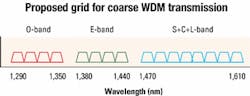

One organization working to define standards for CWDM systems is the 1,400-nm Commercial Interest Group, whose participants include component suppliers, system vendors, and service providers. The group's focus to date has been primarily on defining the CWDM wavelength grid and investigating the cost/performance comparisons of DWDM versus CWDM architectures.The CWDM wavelength grid under consideration for proposal is divided into three bands. The "O-band" consists of 1,290, 1,310, 1,330 and 1,350 nm, the "E-band" consists of 1,380, 1,400, 1,420, and 1,440 nm, and the "S+C+L-band" consists of eight wavelengths from 1,470 to 1,610 nm in 20-nm increments. These wavelengths take advantage of the full optical-fiber spectrum, including the legacy optical sources at 1,310, 1,510, and 1,550 nm, while maximizing the number of channels. The 20-nm channel spacing supports lower component costs with the use of uncooled lasers and wideband filters. It also avoids the high-loss 1,270-nm wavelength and maintains a 30-nm gap for adjacent band isolation (see Figure 5).

CWDM systems development and standards efforts come at a critical time for metro-access service providers. As the demand for bandwidth is pushed to the edge of the network, the need for low-cost transport systems is imperative. Today's CWDM technology fits these requirements, offering a scalable system architecture for metro and access networks.

Marcus Nebeling is president of Fiber Network Engineering Inc. (Livermore, CA). He can be reached by phone at 925-456-5340 or by e-mail at [email protected].

Address letters to:

Letters to the Editor

Lightwave

98 Spit Brook Road

Nashua, NH 03062-5737

e-mail to: [email protected].

Include daytime telephone number.

Letters may be edited.